From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

While the Chow family is well known in Sault Ste. Marie for their years of running Victoria House (The Vic), another member of the family made a name for himself by a completely different means.

Lewis Hong Chow grew up in Northern Ontario and Canton, China. In Sault Ste. Marie, his parents owned and operated the Victoria Hotel on Pim Street. Throughout his childhood, Lewis remembered spending hours watching planes take off and land in the river. The Ontario Provincial Air Service had built their new aerodrome just behind the Vic, where the Bushplane Heritage Centre is now, meaning that Lewis was constantly exposed to what he called “the golden days of aviation in Canada.”

All of those hours spent watching planes sparked a dedication and passion for flying. He attended St. Louis University in Missouri, graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Engineering and Aviation. Almost immediately after graduation, upon returning home, Lewis was offered an engineering position with de Havilland, a prominent aircraft manufacturer.

In 1941, Lewis began work on the Mosquito, a WWII bomber and one of de Havilland’s most well-known planes. The plane’s largely wooden frame earned it the nickname “The Wooden Wonder.”

The following year, Lewis accepted a position at Noorduyn Aviation, working on the Norseman and Harvard aircrafts. Shortly after, however, he was recruited to join the National Research Council’s Mechanical Engineering Division, working in their state-of-the-art labs. At the NRC, he became involved with multiple projects, including testing alternative fuels, finding solutions for overheating engines, and working as an RCAF flight-test engineer, all significant contributions to the war effort.

With the end of the Second World War, Lewis moved on to a new stage in his engineering career. He landed a position with A.V. Roe Canada, also known as Avro, on the CF-100’s preliminary design team. However, he soon opted to pursue his passion for testing new planes, a career choice that brought him to Canadair, where he worked as an experimental engineer. Among his accomplishments was his work on the F-86 Sabre, the fastest plane in the world at that point. During his years at Canadair, he also moved into the business side of things.

However, it was his work on the Sabre that Lewis considered the pinnacle of his career – and his contributions to breaking the sound barrier. While many had tried to travel faster than the speed of sound, it was not without its risks. Geoffrey de Havilland Jr., son of de Havilland’s founder, died during an attempt when his plane broke up. Around the same time, however, Major Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier successfully.

And in 1953, Jacqueline Cochran broke the sound barrier, making her the first woman to do so. She flew an F-86 Sabre, and Lewis Chow was a member of the support crew. The attempts were risky due to the high speed, and Lewis remembered multiple flights with late nights and early morning starts. Jacqueline Cochran also spoke with him personally about the workings of the aircraft during some of their training flights. And she would invite the Canadian crew to her lush California ranch to spend a weekend. After the record was broken, she wrote thank you letters to the crew; the letter to Lewis read in part, “I know that without your fine help and cooperation, my records would never have been realized.”

In the 1960s, Lewis began working for Pratt & Whitney Canada. He worked there for twenty years, retiring in 1986. Throughout his working life and into his retirement, he became involved in numerous humanitarian efforts, including fundraising for and then serving as the president of the Montreal Chinese Hospital. He acted as a consultant with the University of Ottawa Heart Institute to liaise with engineers and develop an artificial heart, using a turbine as a model, a lifesaving medical advancement. His humanitarian work was honoured with a Governor General’s Commemorative Medal.

Lewis Chow died in 2015 in Ottawa at the age of 97. He was predeceased by his wife and one of his daughters, and he left behind two other children and several beloved grandchildren – including one granddaughter named after Jacqueline Cochran.

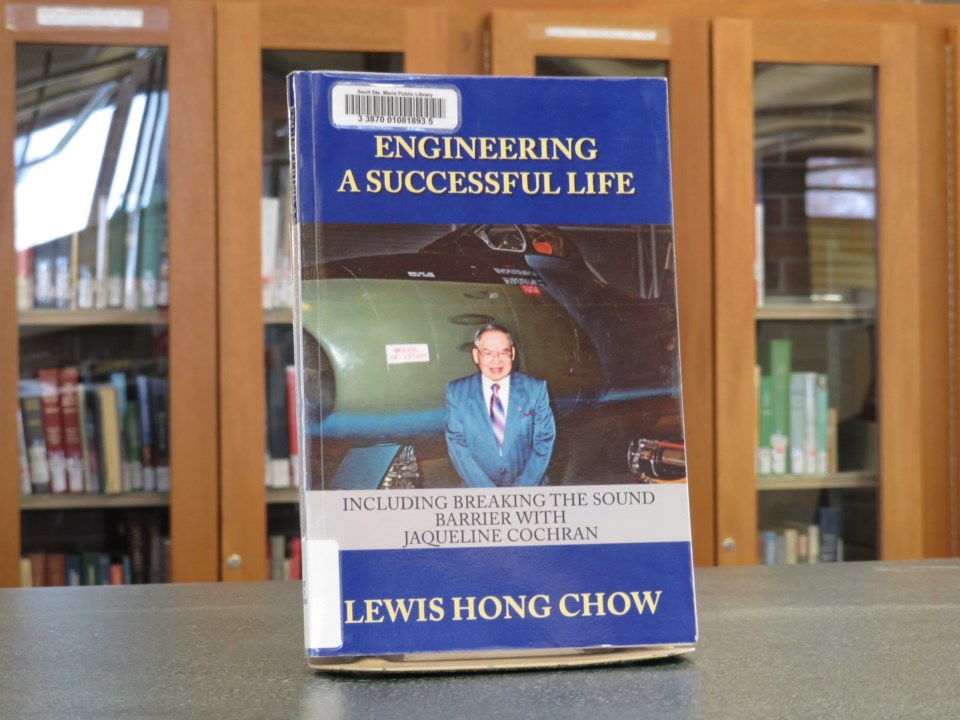

He also left behind a fascinating legacy – told in part through a memoir he published entitled, Engineering a Successful Life. The book included details of his career as well as lighthearted family stories of fishing and hunting trips. He also related that since he was such an avid photographer in the 1930’s he made his own darkroom to save on film developing costs.

In the introduction to Chow’s memoirs, a longtime friend noted the “instinctive modesty” and “abhorrence of self-serving bravado” that impacted the writing process. Perhaps that is why, throughout the book, Lewis Hong Chow referred to himself only in the third-person, describing his life as though from an outside perspective.

Lewis Chow’s legacy also continues through a permanent exhibit at the Canadian Bushplane Heritage Centre. He was a trailblazer – believed to be the first Chinese-Canadian aeronautical engineer – and an accomplished member of Sault Ste. Marie’s famous Chow family.

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provides SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more Remember This? columns here