When George Al Khoury, returned from Barbados to be with his parents in Damascus in Syria in 2010, the last thing he expected was to become displaced from his home country and find himself in the middle of a war. Three months later, as Al Khoury noted in his talk at Ermatinger-Clergue National Historic Site’s Heritage Discovery Centre theatre, his world “was turned upside down.”

For Al Khoury, returning to Syria was never part of his original plan. “When I was 19 years old, I did my military service, so after that, I decided to leave the country and never go back.” But it was the constant call of his family that made him decide to go back. By early 2011, the unrest in Syria that had grown out of discontent with the Syrian government had escalated to an armed conflict after protests calling for the removal of the country's president Bashar al-Assad were violently suppressed.

“Nobody ever thought that this might happen … We always used to keep to ourselves where we come from in my country. We kept to ourselves and never did anything wrong to anybody. We always just wanted to live safe and happy.”

Like many Syrians, Al Khoury fled to Lebanon. Unlike many, he was fortunate enough to have a place to stay in Beirut and had some money to live off. “We thought that it would be a very short time until the war would be over, the [Hezbollah] regime would go away or something would happen like everyone was promising us on TV.”

It was in Beirut, that Al Khoury started to hear stories about the thousands of people who were displaced, and had walked across the border, traveling great distances to the camps “I decided to work with refugees and volunteers.”

He volunteered with Première Urgence Internationale (a non-profit, non-political, non-religious international NGO that helps civilians who are marginalized or excluded as a result of natural disasters, war and economic collapse), World Food Program, United Nations as a food security officer, and eventually became a freelancer who worked with journalists, filmmakers, photographers, and professors from different universities from around the world.

“All I wanted to do was help,” said Al Khoury. “I saw people that I grew up with come to collect food vouchers to eat with their kids. So with a few good friends, we decided to start going to the camps on our own, even at the border between Syria and Lebanon, to take food with us to help people survive, both on our own and with the help of some other organizations.”

During those trips, Al Khoury would also bring his darbuka, a popular drum used in the region's music.

“The first time I played it, all the kids from the camp and other camps came with the sound,” he said. “I found out how important it was to do this, just to be present and say I’m coming with you to those camps. I am coming with a bag of rice or music. Spending some time with them made these people the happiest. They don’t feel they are so alone, in the middle of nowhere, in a tent.”

On one of those visits, someone took a video of Al Khoury playing with these kids. One of Al Khoury’s friends suggested they begin filming their interaction with the children and other folk musicians in the camps.

“The idea at the beginning was to just follow different musicians, to keep them company . . . support them to play their music, to help others play their music, to encourage others, especially kids to play these instruments. Then the idea expanded to become a documentary.”

The friends initially began using only a cell phone to film, but eventually acquired a camera and sound equipment. For three years, they followed over eleven musicians from nine different camps.

It was during this time, Al Khoury met Michael Friscolanti, formerly a senior writer for Maclean’s Magazine, who was working on a cover story for the magazine entitled, Saving Family 417. With help from Friscolanti and the Canadian government, Al Khoury eventually came to Canada in 2017, and made Sault Ste. Marie his home. Despite Al Khoury’s departure from the war torn region, the work on the documentary continued.

“My partners in the documentary are taking care of all these guys. They have even taken some of them into the studio to record them proper songs, hiring songwriters, well known in the region to help write songs,” he said. “The special thing about our documentary is that we believe in music and the power of music. We were just driving our own car, using our own money and instruments, or anything we could to be with these people. I think some of these [musicians] they will remember us for all of their lives . . . They don’t look at music as something you can make money off of, only how rich and how important it is for our soul.”

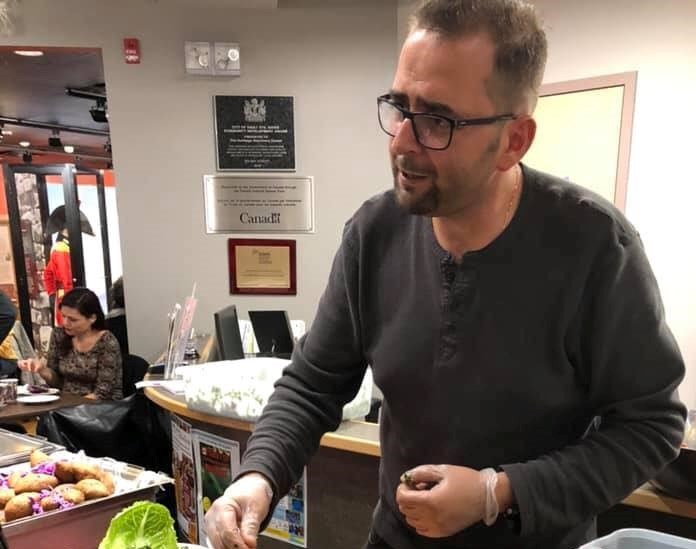

Al Khoury gave his talk and showed raw clips from the Songs of the Departed documentary to a packed house at the Ermatinger-Clergue National Historic Site’s Heritage Discovery Centre theatre as part of 10th Annual Sault Ste. Marie Culture Days. The event was hosted in partnership with the Local Immigration Partnership.