From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

As the Great Depression hit Northern Ontario, one of the more visible signs of economic distress was the creation of “jungles” - communities of ramshackle shelters put together with whatever building materials were at hand.

As people found themselves evicted from their homes, or travelling to new communities in search of better work prospects, they often wound up joining these jungles.

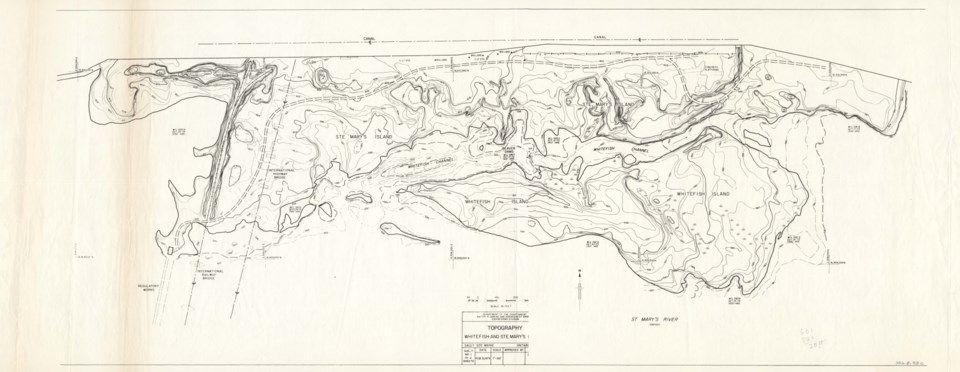

In September of 1931, Sault Ste. Marie residents were shocked to learn that one such jungle was located on Whitefish Island, near the canal.

Rotary Club member Wilfrid Walker found out about the jungle accidentally when he saw a number of people bringing food to Whitefish Island. He visited the area himself to see what was going on, and then alerted the Sault Star about what he found.

He returned, accompanied by a Sault Star journalist who wrote about the living conditions there, and the desperation and hopelessness he witnessed. The two toured Whitefish Island, speaking to inhabitants and handing out food that had been donated. The food “vanished like snow in May sunshine,” many using their clothes as makeshift bags to bring items back with them. There was concern that some of the inhabitants did not have the pots needed to cook the dried beans that were handed out.

A wide range of people found themselves living on Whitefish Island, including longstanding city residents, seniors, and veterans of the First World War. Most of them were single men, who did not receive as much support from local relief efforts. Those living there estimated that there were approximately 200 inhabitants.

“We haven’t done anything bad,’” one inhabitant of the jungle told the Sault Star. “We just can’t get work and that is no crime.”

Hungry and desperate for employment, the people in the jungle may have effectively done away with class barriers. “Good clothes mean nothing,” the headlines proclaimed, referring to people who had once been well-off but now found themselves dressed nicely but starving. Ethnic divisions, however, still lingered, with people dividing into groups based on their nationality – Italian, Finnish, French and Swedish. The Sault Star reported that there was one lone Ukrainian on the island, and he found “there [was] no place for him among the various camps.”

Some slept in boarding houses overnight, coming to the island to cook and eat because they had no adequate place for food preparation. Others were there more permanently. They lived in shelters constructed from the roots of overturned trees, saplings, strips of cloth, and pieces of canvas; none of these afforded much protection from the elements. Some weren’t even that lucky, sleeping in open air without any blankets or shelters.

Much of their food was donated to them by individual people or by local businesses. One resident had a man give him a bag of oatmeal; bakers gave out bread; at least one butcher was suspected to be handing out scraps of meat that were normally saved for dogs.

After the news of the jungle broke in the Sault Star, more citizens stepped in to help. Donations came in of food, with the Globe and Mail reporting that “half a ton of groceries” had been brought in. Candelori and Travaglini of James Street provided 200 pounds of free sausage to those living on the island – they just had to visit the shop and ask. On top of food, people also donated tobacco, blankets, and even tents.

While their circumstances were still far from ideal, inhabitants were elated and relieved, telling the Sault Star, “We have nearly everything we need.”

In September of 1932, one year after the jobless jungle first gained media attention, newspapers reported that conditions had improved. According to the Globe and Mail, while more people were unemployed, relief efforts meant that there was no need for an extensive jungle on Whitefish Island anymore.

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provides SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more Remember This? columns here