From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

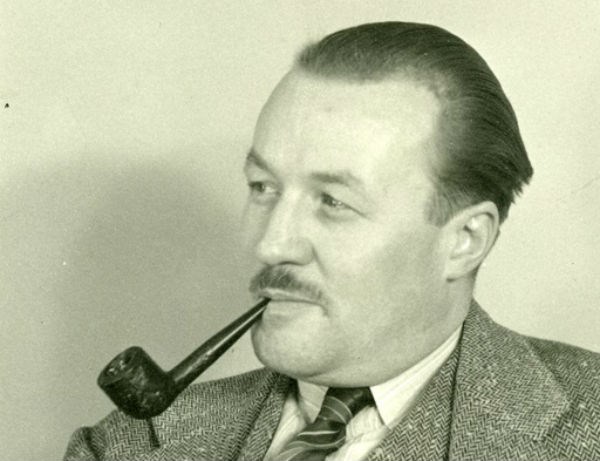

In 1966, Sault Ste. Marie was gripped by an ongoing court case: Dalton Barber, an Algoma Steel executive, was facing charges of capital murder in the death of his wife, Marjorie.

However, while investigators had a motive in the form of another woman, a cause of death, and even a confession, they failed to prove exactly how Dalton had allegedly filled the bedroom with a lethal amount of carbon monoxide.

However, Dalton’s cleaning lady had come forward, just prior to the start of proceedings, saying she had found a partially-burned hose in the fireplace. She had tossed it out into the backyard, not thinking much of it until suspicion started to mount against Barber.

It was a discovery that prompted Bob McEwen to declare, “I think we may have solved our problem!”

Enter the work of forensic scientist Douglas Lucas, employee at the laboratories of the Attorney General, brought in from Toronto to investigate. On May 13, nine days after the trial started, he ran a late-night experiment, accompanied by defense lawyer Terry Murphy, three members of the police, Dalton’s brother Jack, two Algoma Steel technicians, and a mechanic.

Lucas used a garden hose, running it from the exhaust pipe of one of the Barbers’ vehicles, up and through the bedroom window. Samples indicated that this would quickly fill the room with a deadly level of carbon monoxide – enough to kill her in “[possibly] less than two minutes.”

Tellingly, the experiment also left Lucas with black smudges on his hands. However, Lucas had soot on the palms of his hands, and Dalton was found with soot on the back of his hand, a discrepancy that Terry Murphy requested be recorded. The evidence was noted, Lucas washed his hands and, in doing so, discovered that the soot was being transferred from the palms to the backs of his hands, matching Dalton Barber.

This revelation, according to Lucas’ memoirs, prompted Murphy to say, “I think I’d better go and have a conversation with my client.”

The experiments wrapped up later than 2:30 a.m. the following morning. The jury saw the results just a few hours later when Lucas testified. It was last-minute, damning evidence.

However, Murphy maintained that his client did not kill his wife. “He may be socially despicable . . . but he’s criminally innocent,” he said.

He sought an acquittal for Barber, arguing that the confession should be disregarded, and that Marjorie had committed suicide. Even the forensic evidence failed to explain many details about the case – including how Barber could have burned the garden hose in the fireplace after Marjorie’s death without filling the house with the smell of burnt rubber. The garden hose could have just as easily been used for yard work.

Meanwhile, special Crown prosecutor Caldbick argued that Barber was “a monumental liar” who would “lie about anything.” He said that Barber was clearly laying the groundwork for Marjorie’s death, and he had motive to kill her.

On May 18, the case was officially in the hands of the jury.

The trial was “probably the longest murder trial” held in Algoma up until that point, according to the Sault Star. People were evidently anticipating a long jury deliberation as well: the wife of one of the jurors told the Globe and Mail that if there was a verdict that night, “we’re gonna get drunker’n hoot owls.”

Ultimately, the jury only deliberated for eight hours and 20 minutes. Later that day, Dalton Barber was convicted of non-capital murder – meaning that the crime was considered to be unplanned and undeliberate.

Dalton was sentenced to life in prison. The accused sat with his jaw clenched but did not react to the sentence; Irene Chapman, according to the Sault Star, “wept quietly.”

He spent much of his sentence at the Kingston Penitentiary before receiving parole and moving in with a family member. His defense lawyer, Terry Murphy, went on to become an MP and judge. One of the Sault Star reporters initially covering the case, Brian Vallee, would become a prominent author, particularly on the topic of domestic violence. Inspector Bob McEwen, heavily involved throughout the case, became Chief of Police in Sault Ste. Marie. Forensic scientist Douglas Lucas became the Centre of Forensic Sciences’ Director; amongst his many contributions to the field, he pioneered the use of roadside breathalyzer tests.

It was a grueling case: lengthy, for the time, and filled with contradicting statements and testimonies. What started off as “an unfortunate accident” ended with a man serving time for murder, and a city enthralled by the personal details of those involved.

This ends the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library archive's four-part series on the Dalton Barber Case:

Part 1: The mysterious death of Marjorie Barber

Part 2: Sault Ste. Marie's trial of the century begins

Part 3: A mystery woman appears

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provides SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more Remember This? columns here