From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

In 1914, World War I ushered in a dark chapter for Canada with its treatment of immigrants — and with it, a dark chapter in Sault Ste. Marie history.

In the years leading up to the First World War, attitudes toward many European immigrants took a turn for the worse in the city. Sault Star articles discussed the dangers of immigrants carrying knives and criticized the city’s “foreign problem.” In one case in 1912, two Austrian men, Mihal Konic and Pete Michaelsen were stuck on the ferry, going back and forth between the two Saults for almost four days because neither country wanted to allow them entry.

Once World War I began, those attitudes only worsened.

During the war, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a major world power, was considered an enemy of Canada. The empire itself covered parts of modern-day Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Ukraine. People with backgrounds from those countries, particularly Ukrainians, were labelled as “Austrians” and treated with suspicion and animosity. Most had no loyalty to Austria whatsoever and were simply in Canada seeking the opportunities and freedom they had been promised.

With the passing of the War Measures Act in 1914, suspicion and animosity turned into government action. The Act gave the government power to deny rights to “enemy aliens” — seizing property, deporting people, restricting travel, and requiring that they carry identification cards at all times. These regulations even applied to citizens, provided that they were from backgrounds that the government deemed a threat: largely Austrians and Germans.

Those affected needed special permission to travel, and often could not leave the country on the grounds that they might fight for opposing military forces. They could not own vehicles, their possessions could be seized, they could not send money overseas to family in Europe, many lost their employment, and they eventually lost any voting rights they had.

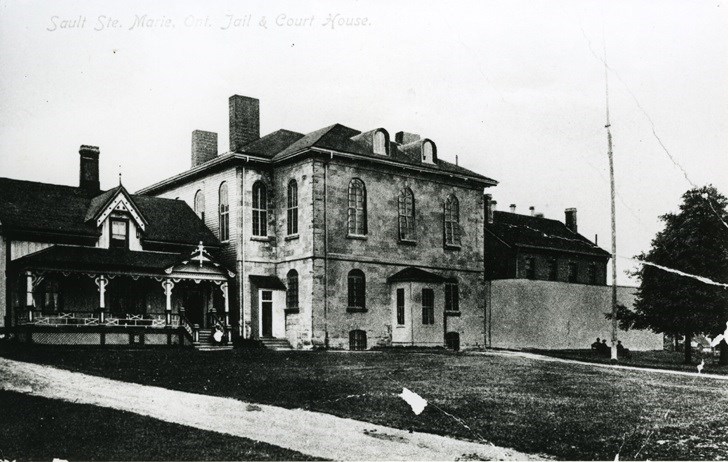

“Enemy aliens” also had to check in regularly with police. Over the course of the war, approximately 1,500-2,000 Sault Ste. Marie residents had to report to police each month at the court house on the basis of their ethnic background; for context, over 80,000 people across Canada were required to regularly check in with authorities.

While at the court house, they also were required to pay a poll tax: a flat fee that would result in additional fines or jail time if not paid. Sault Star articles praised the amount of money collected, “mostly from Aliens in the west end of the city.” In 1917, the Star wrote of how “unfortunate” it was that the poll tax had been lowered from $5 to $3. After all, the article claimed, Austrians did not have much faith in the Canadian banking system and usually carried large amounts of cash on their person — “at least $200,” said the sergeant in charge of collecting the tax. It would have been “just as easy” to get more money out of them.

In that political climate, it’s not surprising that people would try to leave, particularly for the United States. For the first part of the war, the US remained neutral in the conflict, meaning that it would have been an attractive option for people looking for jobs or a less restrictive way of life.

In 1915, the Sault Star reported that a group of Austrians had constructed a large raft for the purposes of crossing the St. Marys River into Michigan at the east end of the city. At one point, a group of 30 people was rounded up by officers in association with this escape attempt.

And they could get help with their escape, too. Some locals would smuggle people across the border into the States…for a fee. According to news reports, the going rate was around $3-4 per person smuggled across — or, in some cases, as much as the smugglers could get out of their passengers.

While it may have initially helped their wallets, helping Austrians across the border into Michigan did not come without its consequences for the smugglers. There was at least one instance of a man being brought up on treason charges for his role in helping Austrians out of Canada; a grand jury found there was not enough evidence to indict him. In another case, a man spent four and a half months in jail in Michigan, a month in jail in Canada, and was fined $100 dollars for carrying “alien enemies” across the river from Point Aux Pins.

While these were isolated incidents, local authorities and Colonel Penhorwood, in charge of the militia, thought there was something more organized going on. Speaking with the media, they expressed their suspicions that there was a network operating to help people flee the country.

However, the worst was yet to come. In late 1914, the Sault Star reported that the government’s plans were “maturing” for how they were going to treat aliens. The plan was to take those who were “a menace to the community” and those who were out of work and assign them manual labour – a plan that continued to unfold over the course of the war.

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provides SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more Remember This? columns here