Eddie Benton-Banai is worried because very few Anishinabe know their own creation story.

Benton-Banai was raised by the women of his lodge to become grand chief of the Three Fires Midewiwin Lodge in 1986, presiding over a spiritual tradition encompassing the Maritimes, New England and Great Lakes regions. He's academic and spiritual advisor to Shingwauk University, known to many of his students and peers in Midewiwin as Bawdwaywidun.

The Shingwauk positions, Benton-Banai maintains, were not given to him because of his heritage.

He became grand chief because he was born into the Midewiwin traditions and chose to uphold his trust responsibility to share those teachings.

To do the work, he says.

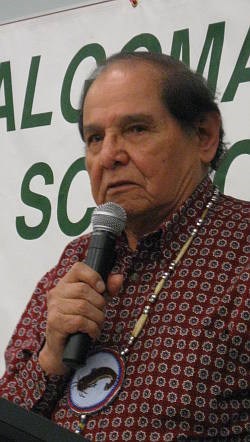

He is shown speaking to and Algoma District School Board conference in 2008.

Benton-Banai, is a full-blooded Ojibwe-Anishinabe of the Fish Clan from the Odawazawguh i gunning or Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation in Northern Wisconsin.

He spends much of his time in Sault Ste. Marie, attending or overseeing teaching, ceremonial and sweat lodges as the Midewiwin leader in a very active community.

"One cannot know where he is going lest he knows from whence he came," Benton-Banai told SooToday.com this past week. "I inherited these words from my grandfather, who inherited them from his grandfather.”

Two weeks after a historic Three Fires Midewiwin Lodge gathering at Garden River, we sat down with him in his office at Shingwauk University to find out more about native spirituality.

We asked only one question.

More than an hour later, we walked out of his office with a superficial understanding of the rich, complex and long-lived traditions of the Anishinabe.

In answer to the question "What is Midewiwin?" Benton-Banai embarked on a story that spanned more than 40 years.

"Before civilization came to our land, every person knew our creation story. Every child heard the creation story while yet in the womb. They learned what their clan was and they heard their clan song because their fathers sang it to them while they were yet in the womb," he said. "I am describing to you traditions that almost no longer exist."

Before civilization, Anishinabe children heard these things from before they are born.

So they understood the essentials and responsibilities of the clan, the structure of the society, who they were and how they came to be in the world.

Benton-Banai was one of those babies.

He heard these things while he was yet in the womb, but still after civilization came to this land.

His parents and his grandparents sang him the songs.

He wasn't allowed to go to school until he was nine and he spoke only his own language until he started school.

"It's now coming out that there were predictions that I would have some responsibility," the grand chief said. "But being born into these traditions and raised with all of those hopes never prevented me from doing things I wanted to do."

Benton-Banai's parents and grandparents also taught him Midewiwin teachings handed down for countless generations.

"For that I thank them every day, because I think that without them, where would I be?" he said. "In prison doing life? In some prison listening to the train go by? Long dead and buried?"

In the early 60s, Benton-Banai started taking these teachings to the Stillwater State Prison in Minnesota to share with Anishinabe inmates who wanted to learn more and to live the teachings.

From that sprang all of the native prison programs in both the U.S. and Canada and it was the beginning of Benton-Banai's journey on the path of culture-based education.

It also led him to the American Indian Movement, for which some credit him as being a founding member.

"The American Indian Movement was saying something that I thought was very important, so I went there," he said.

"The FBI says I was a founding member," he says with a laugh.

"But I don't take credit for that. It would be a lie for me to say I am the founder. It came through inspiration. It came through revelation - if you want - and through the willingness to pick it up."

Some of the teachings Benton-Banai shared in his role as spiritual advisor to the American Indian Movement included the prophecies of the Seven Fires.

These prophecies foretold the coming of the light-skinned race 500 years before any of them arrived in the Americas.

Again, 300 years before Europeans arrived, the Anishinabe, or the people who were lowered from the spirits, were reminded that visitors would be coming and they should prepare.

"'You will some day know the truth of these words when the rivers will run with poison and the fish will become unfit to eat,' the people were told," said Benton-Banai. "A people who had never seen pollution, who had never seen white people, said all of these prophecies that are being given to you."

Now that those times are upon us, it's clear we are living in the time of the Seventh Fire, as prophesied by Midewiwin leaders hundreds of years ago, he said.

As prophesied, the people have gone away from their own ways and forgotten the teachings.

Now, it's time they are reminded, said Benton-Banai.

The poisoned rivers are not a warning to the white people.

They are a reminder to Anishinabe that it's time for them to listen to the heart of the Creator.

"In the classes that I teach, I have yet to run across either a teacher or a student who gives any credence to Anishinabe theology, philosophy or history, accept that which they read in books written by the conqueror," he said. "These books are often hate-filled and ignorant. But while I describe that, I also describe our own people because they are often as ignorant as they are."

Click here to read the conclusion of this article